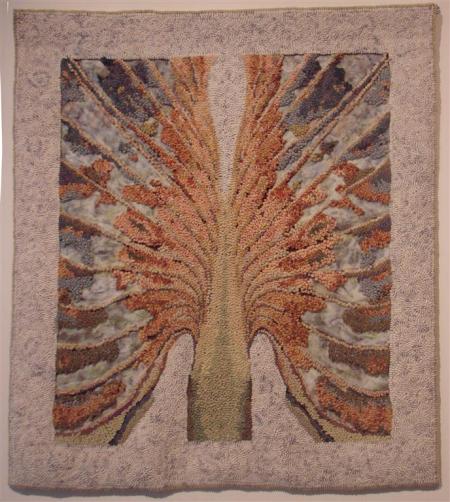

Diva, Jim Gislason, Oil on mesh pinned to canvas

About three months ago, I had dropped in unexpectedly at the Elliott Louis Gallery hoping to see the gallery owner Ted Lederer. He wasn’t there and his able assistant, saying he might arrive any moment, began to distract me with some of the latest work in the gallery.

It was the first time I had heard of Jim Gislason and ergo, the first I had seen his creations. She explained his technique whereby he prepares a photomontage of images which he then translates into a photo transfer on emulsive film for silk screening, and then he proceeds to force oil paint through the developed silk-screen. It’s a labour intensive process and it requires a complete fore-knowledge of the final image because, at the point in the process that the oil paint is being pushed through the silk screen material, all has to be done at once.

Since he has differing depths of extruded paint coming through, he needs to know exactly at what place he is pushing through with which colour and a fairly precise amount of paint. That’s all rather technical, so of course I was impressed at the complexity of it. Nevertheless, if the process isn’t in tandem with some meaning, then it’s futile to try to impress someone with the number of layers of paint or the hours it takes to dry.

Detail of paint extrusion. Note the icon of Thor’s hammer from the painting Reveille, J. Gislason

Details of paint extrusion and paint manipulation, glazing etc.

At that time, there were only a few of Gislason’s works and I found them quite engaging. I had to refrain from touching them, they were so tactile, yet every inch of each of the works had something more going on in them. The texture was made up of a lexicon of printers’ symbols mixed with new icons made by Gislason himself. He photographs images he wants to use and then reduces them to a size of the printer’s symbols, mixing up the ready made with his home-digitally-made new symbols, and creates a large mass of them.

From far away, the image looks quite serene – large abstract shapes that glow with colours vibrating against each other, which are filled with details on closer inspection.

So are these paintings or are they silk screen prints?

If they must be classified, I’d put them with the former category. They are, after all, made with oil paints, not silk screen inks. Secondly, there is only one image made each time through the prepared silkscreen, thoroughly dried, touched up with more painting on the surface and then it is removed from its stretcher bars and the screen with its extruded image and additions of paint are pinned to its canvas lined exhibition frame.

Framing detail, mesh pinned to canvas

When finally the gallery owner came in that day, I was scrutinizing one of these works and was somewhat reluctant to withdraw from the process of inspecting the details of the imagery. After we had talked, he sent me home with his only copy of a printmaking anthology in which Gislason’s work figures along with an explanation of his ideology. Not only is Gislason an artist but he is a wordsmith as well. His poems are sometimes part of the imagery and sometimes published beside the work of art.

Last week, the e-mail invitation came announcing Jim Gislason’s latest show and the opening reception and I noted it in my day-book. Not long after, I had a separate e-mail from Ted saying, “If there is only one exhibition you come into town for this year, make it this one. No kidding!”

Fortunately, I had Thursday March 11th available and it was a perfect opportunity to do a bit of gallery hopping with my sister who is in town from Rossland for her first solo show. I had no hesitation. In fact, I made sure we were there a half an hour early so that we could see the show clearly without others to interfere in either our concentration nor our enjoyment of the imagery.

As guests arrived, Ted came by to say Jim Gislason would be arriving shortly and I just had to meet him. When the two of us met, there was a momentary awkward pause when Ted disappeared. Jim had no idea who I was and though I had become familiar with his paintings I didn’t know what to expect either.

I explained myself – my admiration for his work and my desire to write about artists I appreciated so that good work could become more widely known. I talked about the layers of meaning that I was discovering in his paintings. He expressed his concern that people would only focus on the technique and not get the messages built into the work.

Work on paper, Jim Gislason from an earlier series. Note the chevron pattern that occurs here in black and white on the left and in grey and white on the right. This pattern recurs in different colours in many of his paintings.

Although there are a few pieces from earlier series, the greater part of this Gislason show is themed, Kings and Queens. In each of the newer images, he represents historical faces of either a king or a queen. The kings and queens, he says, are not mythical people or heads of state, but ourselves, living to the greatest of our potential.

The refusal of Charon, Jim Gislason, Oil on mesh pinned to canvas

He has a strong belief in spirituality gained from wide reading and experience in several religious philosophies, Buddhism being the one that more prominently underpins his work. I asked about one cross-like symbol, but it was, he explained, Thor’s hammer, or a Mjollnir. The Longships I and II represent a square-sailed Viking vessel.

Longship II, Jim Gislason, Oil on mesh pinned to canvas

I had to look up the reference to Thor’s hammer later as I was unfamiliar with this – so I am providing this quote from Wikipedia:

- The Prose Edda gives a summary of Mjöllnir’s special qualities in that, with Mjöllnir, Thor: … would be able to strike as firmly as he wanted, whatever his aim, and the hammer would never fail, and if he threw it at something, it would never miss and never fly so far from his hand that it would not find its way back, and when he wanted, it would be so small that it could be carried inside his tunic.[1]

Besides the spiritual aspect, his references are drawn from various iconography – hand lettering print type, the graphic arts, Egyptian and Greek art, modern day traffic symbols, map making and historical painting references, to name just a few.

Shadow Throne, Jim Gislason Oil on mesh pinned to canvas

For instance, in Shadow Throne, from afar, the figure appears to be dressed in a medieval garment with hoops holding the dress out widely from the body. It is, in fact, derived in shape from Velasquez’s Infanta Maria Theresa of Spain. Up close, though, the panels of the dress are fashioned from antique half- maps of the globe and other cartographic references, adding depth and richness to the overall imagery.

Detail from Shadow Throne, Jim Gislason

When I was speaking with Jim Gislason, I realized that it would take along time to delve into all the references he uses. We discussed this briefly. Though it would enrich my appreciation of his work to know what was embedded in the work, at some point, when the artist lets go of his work, i.e., he shows it to the world, then he must let go all the particulars that he has put into it. Viewers come with their own experiences and knowledge. What may resonate in their minds may not be at all what the artist intended but that does not diminish the work and may in many instances enhance their appreciation.

Medallion, Jim Gislason, oil on mesh pinned to canvas

Detail from Medallion

This is a show worthy of a good long look. Each time one of Gislason’s pieces is revisited, more is found in it, whether be the connections between the numerous symbols used or an appreciation of the paint texture with its glazes and tactile richness, the added elements collaged in or one of his poems that might clarify the image or conversely add some new mystery to it.

In the end, while I marveled at the technique, the focus on that aspect of them quickly gave way to the intricacy of the imagery and the overall abstraction of them. My favorite paintings are the ones where I can’t figure out how they were made (even though I’ve been told) and there is a mystery in the content. I’ve added these to my favorite list for sure!

The show is on until April 24th at the Elliott Louis Gallery at 248 East 1st Avenue in Vancouver, B.C.

http://www.elliottlouis.com/